Great architectural styles were rarely locked in stone: the marble vestments of cathedrals and the gilding of palaces invariably moved – literally – onto wheels. The carriage was the moving calling card of the era: its silhouette could tell whose coat of arms was on the door, which artist painted the panel, and even what the political climate of the court was. From the lush Baroque to the streamlined Art Nouveau, wheelwrights were subject to the same rules of fashion as architects, furniture makers, and tailors, only their “catwalk” passed over cobblestones.

This article traces the changing shapes, proportions and decorative motifs of carriages against the backdrop of six key European artistic styles. We will see how the curl of rocaille turns into austere Doric pilasters and then flows into fragile Art Nouveau. Each stop is four paragraphs of the smell of varnished wood, the crunch of springs and the rustle of silk curtains.

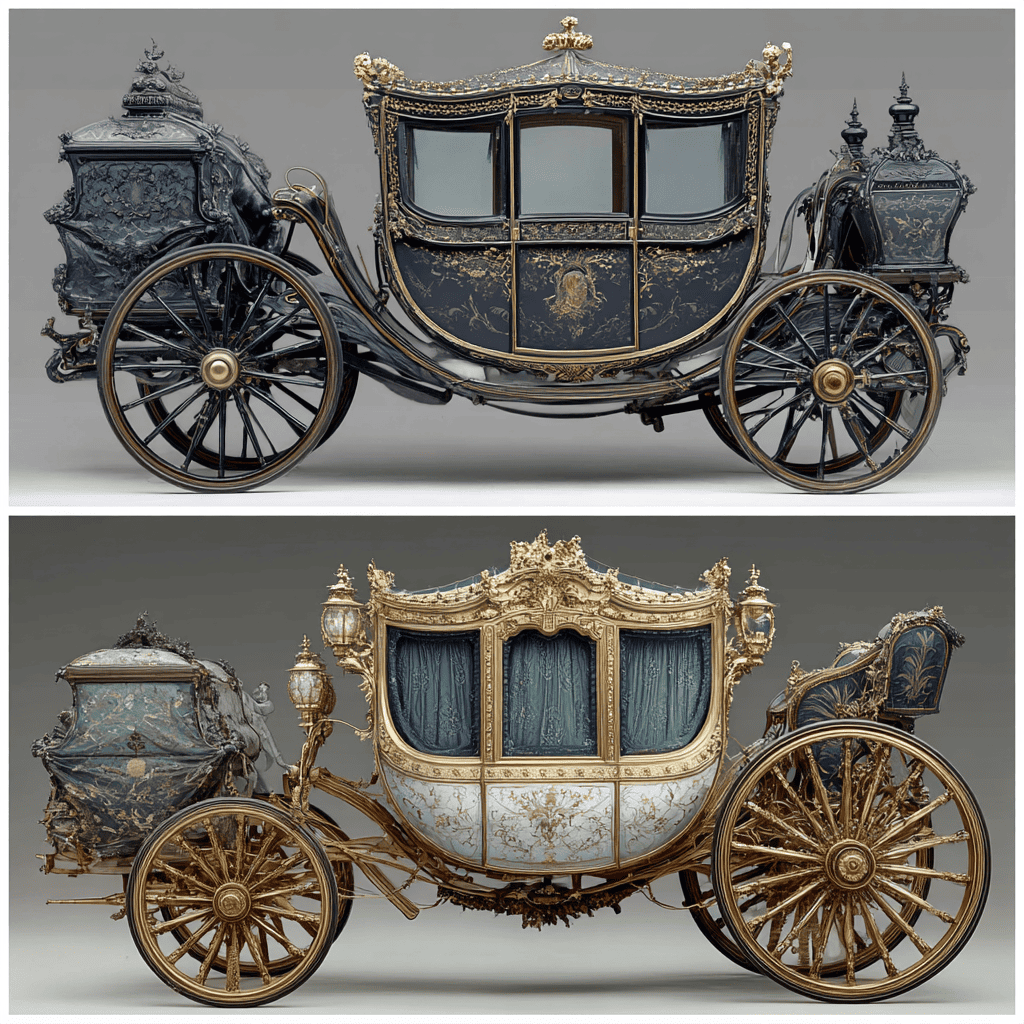

Baroque Chariots of Majesty

The first paragraphs of the carriage’s history are full of weight and glitter. In Baroque, the main thing is the theatrical effect, and the carriages are in keeping with palace scenes: huge compartment-like bodies, ornate coats of arms on the doors, gold in every slit of the carving.

Characteristic features:

○ massive frames with walnut-like stampings;

○ ornate molding in the form of cartouches and atlantes;

○ wheel shields with paintings of biblical scenes;

○ complex pendant design imitating colonnades.

The heavy forms forced the springs to be reinforced; the blacksmiths sought a balance between splendor and the ability to move. As a result, the first “baroque candelabra” appeared – hexagonal lanterns whose play of light emphasized the relief.

These carriages served not so much as transport as a mobile throne: the monarch sat higher than the average passenger, as if on a pedestal, reflecting the idea of “king = living temple”.

Graceful Rococo Curves

When the courts were saturated with pomp, fashion became light and playful. The tone of the carriage was set by rocailles: asymmetrical spirals reminiscent of sea shells turned the massive box into a lacy cocoon.

In forges and workshops, carvers moved from massive cartouches to “a-jour” carvings – through-cuts that allowed air and light to play freely on the surfaces.

● New materials: linden instead of oak – easier to cut;

● pastel varnishes: turquoise, salmon, ivory;

● Chinese silk upholstery with phoenix birds;

● smaller wheels to emphasize the intimate feel.

The interior was reminiscent of a boudoir: brocade pillows, secret perfume boxes, miniature mirrors. The carriage became more pleasing than impressive.

It symbolized the cult of pleasure and private conversations. Even the springs softened the ride – a leisurely “promenade” was in fashion, when ladies could endlessly discuss the latest gossip without leaving the carriage.

Classic order on wheels

The French Revolution and the fashion for antiquity cut away the excess of curls. By the 19th century, the carriage had acquired a strict linearity: carpenters took the portico of a Greek temple as a model, only instead of columns, they used vertical door frames.

Details of the new flavor:

○ straight sandrines instead of volutes;

○ dark rosewood color, almost without gilding;

○ brass protectors, stylized as a laurel ribbon;

○ The coats of arms have been simplified to shields with a motto.

The precise geometry improved aerodynamics – the crews became slightly faster and more stable. Engineers introduced the concept of “center of gravity” for the first time when designing the body.

The interior now features a contrast: the matte leather of the seats against the glossy brass candelabra, just as the dark background in the antique halls emphasized the white marble of the statues.

These carriages were the favourites of diplomacy: their austere appearance inspired confidence, and the lack of excesses emphasised the “enlightened simplicity” of the new era.

Imperial splendor of the Empire style

Napoleon revived the idea of empire – and the wheels once again sparkled with golden bronze. Empire style took the grandeur of Rome and the solemnity of a military parade: carriages increased in size, but retained their classical symmetry.

The “semantics of power” became the trademark:

● lion’s paws on the spokes of the wheels;

● sphinx figures at the corners of the body;

● palette black + gold;

● The inside is red velvet, a reference to the purple of the Caesars.

The doors often featured the emblem of the lictors’ bunch, a symbol of power. Instead of soft rocaille, there were clear diamond-shaped panels reminiscent of legionnaires’ shields.

Technically, the Empire style brought multi-layer glazing: thick at the bottom to protect against gravel, thin at the top to let in light. Comfort increased, and the carriage became a “room on wheels.”

The emperor’s ceremonial rides became a choreography of symbols: eagles on the footboards, oak wreaths on the rear pillars – every detail spoke loudly of power.

Victorian Eclecticism and Industrial Leap

In the mid-19th century, England set the tone. The era of mass production had arrived: cast parts reduced the cost of carriages, so fashion became more democratic, but brighter.

Industrialists experimented:

● iron axles instead of wooden ones – they broke less;

● rubber tires for a noisy city;

● panels made of pressed plywood with inlay;

● stained glass windows with heraldic motifs.

The facade could combine a Gothic pointed arch with an oriental ornament, and the interior upholstery could be quilted Chesterfield leather and Japanese brocade. Eclecticism was a fashionable freedom.

The growth of cities gave birth to closed landaulets and phaetons with soft convertible tops – a compromise between a display of status and protection from the soot of factories.

The carriage became a reflection of global trade: Indian ivory, Scottish cloth and American steel were all found on the same body.

Art Nouveau lines and the dawn of the automobile industry

At the turn of the century, the masters tired of quotations from the past and turned to natural lines. The carriage became fluid: the curves tapered off, like the stem of an iris in the posters of Alphonse Mucha.

Art Nouveau hallmarks:

○ wave fittings;

○ peacock-colored enamel;

○ unusually shaped windows resembling insect cocoons;

○ turquoise and olive varnish.

Technically, modernism brought the carriage closer to the car: a brake system with cables, experimental bearings, lightweight steel in the chassis. The aesthetics changed not only on the outside – battery-powered lamps appeared inside.

The emphasized asymmetry of the body meant movement even when standing. The spring pattern included an S-shaped bend, which supported the overall “nervous” silhouette.

With the advent of the engine, many carriage artists became car designers – the experience of creating light, aerodynamic forms proved invaluable.

Over three centuries, the carriage has evolved from a baroque throne room on wheels to a precursor to the automobile. Each style has left its mark: the heavy cartouche gave way to rocaille, the classical pediment was cast in the bronze of the Empire style, and the silk rococo dissolved in the glass of Art Nouveau. Today, restorers read these “pages” in the same way that historians study the facades of cathedrals – after all, wheels have always borne the imprint of time.

Questions and Answers

They wanted to replicate the monumentality of the palaces, so they used massive wood and thick metal elements.

Victorian eclecticism – thanks to the industrial revolution and developed metallurgy.

General principles of aerodynamics and the use of lightweight steel, as well as the design approach of “movement in a line”.